Did You Know?

VIRET’S FATHER, GUILLAUME (WILLIAM), WAS A DRAPER BY VOCATION.

VIRET’S PARENTS BECAME CHRISTIANS UNDER VIRET’S TEACHING.

Viret was raised in a devout Roman Catholic home. After his conversion, he had a tender affection for those still under the bondage of Roman Catholicism. Viret prayed fervently for his friends and relatives, but especially for his unsaved parents, and soon had the joy of leading them to their redemption in Christ.

At length the divine Word delivered Viret from the theocratic dominion of Rome, and he then began to look around him. . . . Alas! what did he see? Chains everywhere, prisoners held fast ‘in the citadel of idolatry.’ He felt the tenderest affection for the captives. ‘Since the Lord has brought me out,’ he said, ‘I can not forget those who are within.’ Two of these prisoners were never out of his thoughts: they were his father and mother. At one time absorbed by the cares of business, at another mechanically attending divine service, they did not seek after the one thing needful. The pious son began to pray earnestly for his parents, to show them increased respect, to read them a few passages of Holy Scripture, and to speak gently to them of the Saviour. They felt attracted by his conduct, and the faith he professed took hold of their hearts. The grateful Viret was able to say: ‘I have much occasion to give thanks to God in that it hath pleased him to make use of me to bring my father and mother to the knowledge of the Son of God. . . . Ah! If he had made my ministry of no other use, I should have had good cause to bless him.’ 1

VIRET WAS ONE OF JOHN CALVIN’S CLOSEST FRIENDS.

Viret and Calvin were great friends. Though when they first met remains a mystery, Viret was present when Farel called Calvin to the ministry of Geneva in 1536. Here Viret worked alongside Calvin for two years, and corresponded with him regularly thereafter when their ministries parted. The Viret and Calvin families were very close; Calvin’s wife Idelette even journeyed to Lausanne to assist in the birth of Viret’s child. Idelette and Elisabeth Turtaz, Viret’s wife, also kept up a regular correspondence.2

VIRET GREATLY AIDED THE BIRTH OF THE GENEVAN ACADEMY.

The Genevan Academy in the time of Calvin was started by Viret in 1537 in Lausanne. When the Bernese magistrates forced his expulsion, Viret brought his academy to Geneva. Most of the instructors were also from Lausanne, including the principal, Theodore de Beze, and nearly 1,000 of his parishioners.

[The Lausanne Academy’s] status as the intellectual center of the Francophone Reformed Church in the 1540s and 1550s has scarcely been noticed. By the mid-1540s, the early evangelical movement in France centered on Marguerite de Navarre’s network was dying out. Before 1558, Geneva was home to relatively few leading Protestant intellectuals apart from Calvin himself. In the years between the collapse of Marguerite’s network and the opening of the Genevan Academy, Lausanne was the place to be. In addition to Viret, Beza, and Cordier, the Greek scholar Conrad Gessner and noted legal expert Francois Hotman also taught at the Academy. The talented faculty drew visiting intellectuals to the city as well. Renowned Parisian jurisconsult Charles du Moulin resided in Lausanne for a time, as did the contentious Reformed theologian, Jean Morely.3

VIRET WAS KNOWN AS THE “ANGEL OF THE REFORMATION” AS WELL AS BEING CALLED THE “SMILE OF THE REFORMATION” BECAUSE OF HIS WINSOME AND GRACIOUS CHRISTIAN CHARACTER.

Professor Philippe Godet, a nineteenth-century biographer [says of Viret], ‘He reflects the Vaudois character, with its lively spirit of bonhomie, its easy tolerance; his work is for us the smile of the Reformation.’ 4

VIRET’S SINCERE CHRISTIAN NATURE MADE HIM RESPECTED BY FRIEND AND FOE ALIKE.

He was by nature a kindly man with a reputation for being gentle and slow to anger. Friend and enemy alike seemed to agree that he was humble and self-effacing.5

Catholic forces captured Viret and 11 other Reformed ministers in a surprise attack during the Third Religious War (1568-1570). The Catholic commander ordered the execution of seven of the twelve but spared Viret largely because of the positive reputation he enjoyed even among his ecclesiastical enemies.6

VIRET WAS HIGHLY PRIZED AMONG THE SWISS AND FRENCH REFORMERS AS MEDIATOR.

Viret often was called upon to mediate disputes between Calvin and various factions in Geneva. He had been sent by Berne to Geneva in 1538 to try to reconcile Calvin and the City Council but to no avail. Again in 1539, he offered to act as mediator between Calvin and the Genevan government but his proposal was rejected. Finally, in 1541, his presence in Geneva served as a pacifying influence upon both Calvin and the civil magistrates during the unsettled and uncertain weeks after Calvin first returned to the city.

Many times thereafter, when disputes arose among the Reformers themselves, Viret was invited to come to Geneva to act as arbitrator between the feuding parties. For example, in 1544, his services were solicited when Sebastien Castellio’s application for ordination was opposed by Calvin because Castellio rejected Calvin’s allegorical interpretation of the descent of Christ into hell, and refused to accept the canonicity of the Song of Solomon. Castellio protested against the refusal of the Company of Pastors to recommend him for ordination and, since he did have some support for his case, requested that Viret be called in to mediate the dispute. Although Castellio did not obtain much satisfaction from the ensuing debate and final decision, he at least obtained a qualified letter of recommendation to help him acquire a post elsewhere and the whole affair was kept from doing any permanent damage to the Reformed movement in Geneva. Castellio apparently felt Viret had treated him fairly at the hearing and harbored no ill feelings against him for he spent some time in Lausanne immediately following his departure from Geneva.7

Viret was called to Geneva twice in 1546 to act as a mediator in two different conflicts. The first involved a certain citizen of Geneva named Pierre Ameaux who had openly criticized certain aspects of Calvin’s doctrinal position and was thrown into prison because of his audacity. . . . Both Farel and Viret came to Geneva to referee the dispute. . . .

Later in 1546, a young minister at Geneva named Michel Cop became extremely irritated when the Council, upon the advice of Calvin and Abel Poupin, refused to suppress a controversial play based on the acts of the Apostles. . . . The Council of Geneva sent for Viret and he was able to calm the young pastor and persuade him to retract his denunciatory statements. In a few weeks the whole affair was forgotten.8

JOHN KNOX COUNSELED WITH VIRET.

The influence of Viret’s ideas on other Calvinists offers a tantalizing possibility for further investigation. Both John Knox and Christopher Goodman had access to his person and writings. Knox was known to have conferred with Reformed theologians in both Geneva and Zurich and, according to a letter from Calvin to Viret, he was supposed to stop off at Lausanne on his way to Zurich in February of 1554, and seek Viret’s “counsel and advice.” Such a lay over would have been both logical and convenient since the main roads from Geneva to Zurich passed through Lausanne. It seems almost certain that Knox did stop and see Viret at Lausanne, for several months later he wrote concerning his recent journey through Switzerland:

My awne estait is this: since the 28th of January, I have travellit through all the congregationis of Helvetia, and hes reasonit with all the Pastouris and many other excellentlie learnit men upon sic matters as now I can not commit to wrytting.9

VIRET WAS BELOVED BY THE GENEVANS.

The Genevans loved Viret. They immediately elected him a minister of the Genevan church, and assigned him a salary of 800 florins, plus 12 strikes of corn and two casks of wine a year. The Council also provided him a commodious house, which Calvin noted was bigger and better furnished than his own.10

Viret went to Geneva and was appointed preacher of the city (March 2, 1559). His sermons were more popular and impressive than those of Calvin, and better attended.11

VIRET WAS A PROLIFIC WRITER, AUTHOR OF OVER FIFTY BOOKS. HIS WORKS WERE BEST-SELLERS IN HIS DAY, AND WERE TRANSLATED INTO MANY LANGUAGES, INCLUDING GERMAN, ITALIAN, ENGLISH, DUTCH, AND LATIN.

. . . his works were best-sellers in France ranking second in sales only to the writings of John Calvin.12

VIRET WAS A POWERFUL AND POPULAR PREACHER.

From 1532 to 1536 our Reformer-Pastor [Viret] proclaimed the reign of God in the streets, taverns, homes, and church; and he did not cease to take part in what was called the “disputes,” theological discussions, which lasted for hours. . . or even days. Even so the gospel spread with men, women, and children receiving it to their salvation.13

VIRET WAS A 16TH CENTURY ‘MEGA-CHURCH’ EVANGELIST.

During Christmas of 1561, Viret preached in the Cathedral before a crowd, attended, at the head, by Royal Officials and the Councils (city magistrates). The 4th of January, 1562, he presided over the second of two Communion services (the first at 5 a.m., the second at 8 a.m.) at which 7000 to 8000 people communed.14

The English Ambassador, Sir Thomas Smith, observed that even during the height of the plague Viret and his colleagues were drawing crowds of from 5,000-6,000 at their daily sermons.15

The climax of [Viret’s] visit at Nimes came on December 24, 1561, when he held a six hour pre-Christmas Communion service in the main Cathedral with nearly 8,000 people in attendance. Viret prefaced the service with a long, moving evangelistic appeal which led several prominent Roman Catholic authorities to make public confessions of their adherence to the Reformed faith before the large congregation.16

In Lyon, preaching out in the open, he brought thousands to saving faith in Jesus Christ. By the power of his divine eloquence he would even cause those passing by to stop, listen and hear him out.17

VIRET AND FAREL LED THE REFORMATION IN FRENCH SWITZERLAND:

It was Guillame Farel and Pierre Viret who brought the Reformation to Geneva, Lausanne, and Neufchatel.

Calvin was present [at the Lausanne Disputation of 1536] and spoke briefly on several occasions but it was Farel and Viret who carried the chief burden of the argument for the Reformed cause. Worth noting was the fact that Viret’s careful and skillful handling of the question of the relation of the civil magistracy to the true Church of God was seconded by both Calvin and Farel. In fact, after the first two days [of the Disputation] it was Viret who spoke most often and for the greatest length of time, and it was he who finally won the day for the Reformed faith. . . . There was a marked increase in the number of adherents to the Reformation including a number of converts from the ranks of the Roman Catholic clergy present at the debate. During the disputation and the three months following more than eighty monks and nuns and over one hundred and twenty members of the secular clergy of the Roman Catholic Church were won over to the Reformed faith, the majority of them due to the efforts of Viret.18

AMONG THE FIRST GREAT REFORMERS IN FRENCH SWITZERLAND, VIRET WAS THE ONLY NATIVE SWISS.

Peter Viret, the Reformer of Lausanne, was the only native Swiss among the pioneers of Protestantism in French Switzerland; all others were fugitive Frenchmen.19

Unlike the French Calvin, Viret was practically a native son, a fellow romand who spoke a similar dialect and shared the same culture as the Genevans. Indeed, there is much truth to Henri Vuilleumier’s assessment, “The Genevans always considered him one of their ministers, and as if he were simply on leave in Lausanne.20

VIRET WAS INSTRUMENTAL IN BRINGING THE EXILED CALVIN BACK TO GENEVA IN 1541.

[Viret] was asked to use his influence with Calvin, and Calvin, in a letter written to him at the same time as his third to the Council of Geneva, gives us the key to the vagueness of tone which he had adopted in his official letter. ‘Thou tellest me that if I abandon Geneva, the Church is in danger. I can answer nought but what I have told thee, that there is no place which alarms me so much as Geneva. Not that I retain any hatred against them, but I see so many difficulties, that I feel incapable of escaping from them. Whenever I call to mind the times past, my heart freezes with terror.’ But Viret knew well that his fears would not go so far as to prevent him from coming, if once he clearly saw it to be a positive duty. ‘Master Pierre Viret,’ says the register at the date of the 28th February, ‘hath showed that it would be very meet to write again to Master Calvin. Ordered that he be written to.’ 21

Calvin later testified that only the fraternal support of Viret during this decisive period made these first months tolerable.22

VIRET WAS EARNESTLY SOUGHT AS A PASTOR IN FRANCE.

In 1561 Viret’s failing health forced him to leave Geneva and seek a healthier climate in southern France. When news of this spread, calls from countless churches poured in, begging Viret to come to their aid.

. . .invitations poured in from churches in Paris, Orleans, Avignon, Montauban, and Montpellier. The leaders of Nimes begged him to remain with them.23

When Viret arrived in France, churches from all over the country sought him out. The churches in Nimes and Paris even sent delegates to Geneva to ask officially for his services.24

CALVIN’S WIFE, IDELETTE, VISITED VIRET’S WIFE AT LAUSANNE TO ASSIST IN THE BIRTH OF HER CHILD IN 1548.25

VIRET EXPERIENCED TWO SEPARATE ASSASSINATION ATTEMPTS ON HIS LIFE.

The first attempt came after ministering in the Abbey town of Payerne. An irate monk violently refuted Viret’s preaching by running him through the back with a sword as he was crossing a field. The second was while in Geneva. The Reformer was given a bowl of poisoned spinach soup. He lay for some time at the point of death. Though he at length recovered, he suffered from the effects of the poison for the rest of his life.

VIRET’S GENUINE CHRISTIAN CHARACTER GAVE HIM A LOVE FOR EVEN HIS GREATEST ENEMIES.

Despite their many attempts at his life, Viret once saved the life of a Roman Catholic priest.

In France, when a Protestant mob was on the point of lynching a traitorous Roman Catholic priest, Pierre Viret interposed his very life to save him from certain death.26

VIRET ATTENDED COLLEGE AT PARIS.

He entered the College de Montaigu at the University of Paris at about the time Calvin was leaving and Ignatius Loyola was enrolling.27

Loyola was later the founder of the Society of Jesus, also known as the infamous Jesuits.

VIRET WAS CALVIN'S CLOSEST CONFIDANT

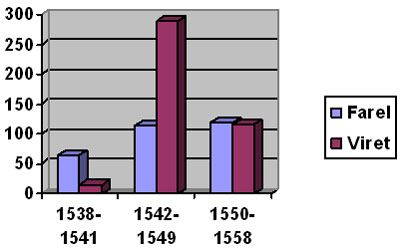

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of Viret’s 1541-1542 stay in Geneva. First of all, Calvin had found the prospect of returning to the city from Strasbourg so abhorrent at first that he likely never would have returned to Geneva if Viret had not been there months beforehand to restore order in the church. Second, Calvin and Viret’s friendship deepened during these ten months together in Geneva to the point where Viret clearly replaced Farel as Clavin’s closest confidant in the following years. According to the extant record, Viret and Calvin exchanged only fourteen letters between Calvin’s exile and his return (1538-1541). During the same period, sixty-five letters survive between Farel and Calvin. In the years following Viret’s departure from Geneva in 1542, however, the figures are reversed. From 1542 to 1549, Calvin was in contact with Viret more than twice as often as with Farel. By 1550, the frequency of Calvin’s correspondence with Viret drops to the level of that with Farel. . . .28

Figure: Calvin’s correspondence with Viret and Farel: Total number of letters exchanged

Back to top of page